As the sun sinks into the wetlands of southern Florida, the sky fills with movement. Small bats twist and dart like sparks in the dark.

But high above them, one bat flies differently. Long wings stretch wide, cutting smoothly through the night air. The Florida bonneted bat does not zigzag like most bats. It glides like a small aircraft, steady and powerful.

This bat is Florida’s largest bat, with a wingspan close to twenty inches. It is also the rarest bat in the United States and one of the rarest in the world. Fewer than 3,000 remain, and every one of them lives in southern Florida.

“Across South Florida, preserving old-growth pine flatwoods and wetland areas appears important for their survival,” stated Dr. Frank Ridgley, who leads the Miami Bat Lab at Zoo Miami. For scientists and conservationists, saving this critically endangered bat has become a race against time. Listed in 2013, the Endangered Species Act (ESA) is critical to the Florida Bonneted Bat’s survival. No other piece of legislation has effectively protected so many threatened and endangered animals. 99% of species under the ESA have seen their numbers multiply and rise towards sustainably healthy populations.

Dr. Frank Ridgley, photo ©️ Zoo Miami

©️Joel Sartore

Bat boxes at Zoo Miami, photo ©️ Zoo Miami

A Bat with Nowhere to Go

The Florida bonneted bat depends on warm, open landscapes and safe places to roost. It once used large trees, palms, and natural cavities across southern Florida. But development has replaced much of that habitat with roads, buildings, and manicured land. Climate change adds new stress through stronger storms, rising heat, and shifting ecosystems. “Across their range, further habitat loss and fragmentation worry me the most for their long-term survival,” reflected Dr. Ridgley, “In urban areas, termite tenting, roof replacements, and construction worries me due to bats liking to roost in buildings when there are no natural roosts available, and the bats are often killed.”

Unlike many other bats, the Florida bonneted bat does not migrate or hibernate. It stays in Florida year-round. That means it must survive hurricanes, heat waves, and habitat loss without ever leaving.

As natural roosting sites disappeared, scientists realized the bats were facing a housing crisis. They needed help.

The Birth of the Miami Bat Lab

Photo ©️ BCI

To answer that need, Bat Conservation International partnered with Zoo Miami to create the Miami Bat Lab. With funding from the NextEra Energy Foundation and support from more than a dozen partners, including state and federal agencies, the lab became a center for research, innovation, and protection.

The goal was not just to study the Florida bonneted bat, but to give it a future.

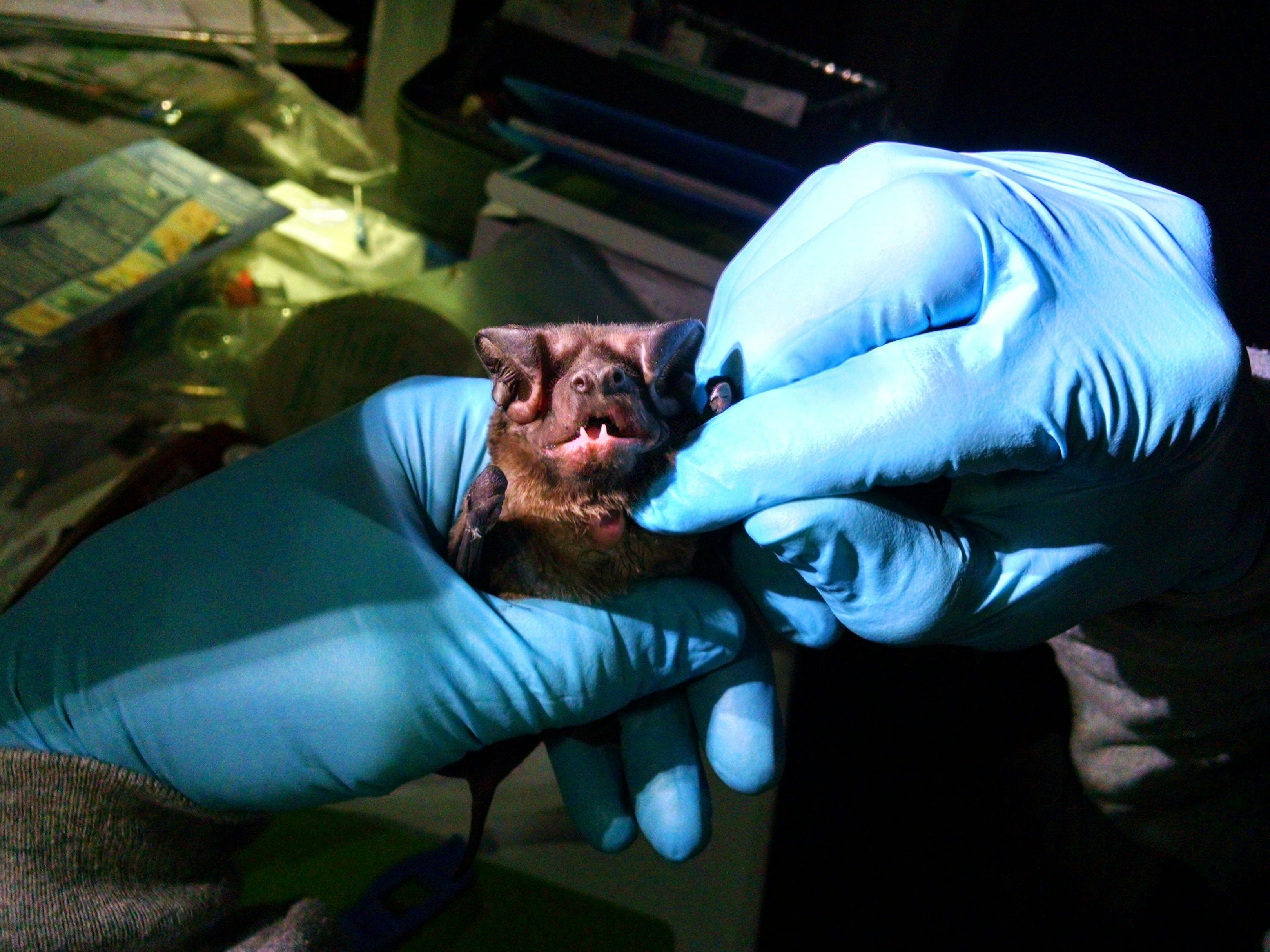

Scientists, engineers, wildlife managers, and educators came together with one clear priority: create a safe shelter for a bat that was running out of places to live along the way. The Miami Bat Lab’s ingenuity led to the discovery of a significant colony of bats, but it was untraditional thinking that led to this find: “If I had just begun studying the species by putting out ultrasonic recorders in the middle of pine rockland fragments around Miami-Dade County, I likely would not have found much evidence of their existence. But, instead, I made a grid including all of Zoo Miami, Larry and Penny Thompson Memorial Park, and Martinez Pineland Preserve, and assigned monitoring points in each grid cell, even if it appeared to be an area completely unlikely to detect one. When I started to process the data, I saw that the bats were not darting among the pines in the pine rockland forest. They were in fact foraging over an unlit parking lot and artificial lakes adjacent to the pine rocklands,” shared Dr. Ridgley, continuing on to say, “If I had just followed the conventional thinking, I would have missed this understanding of their adaptation and use of spaces in the urban landscape. Now we go looking for them on golf courses and other artificial lakes and waterways in areas with good tree canopies where their prey is more abundant and easier to catch.”

Photo ©️ BCI

Rethinking a Bat Box

Bat Conservation International helped popularize bat boxes decades ago. But the Florida bonneted bat is not like most bats. It is bigger, heavier, and has long wings that make tight spaces difficult to use. So the team at the Miami Bat Lab started over. These boxes are large enough for long wings to enter and exit easily. They have two chambers instead of one, giving bats space to move and choose the best spot inside. They are built to survive hurricane-force winds and heavy rain.

Just as important, they create a stable internal temperature. Since Florida bonneted bats do not migrate or hibernate, they need shelter that protects them year-round as the climate grows hotter and storms grow stronger.

Aside from these considerations, Dr. Ridgley shares that they designed a new kind of bat box built for strength, resilience, and comfort and rethought where to place bat boxes given the Bonneted bat’s predators. “The wildlife that mainly interacts with the Florida bonneted bat would be rat snakes, raccoons, rats, and owls. Rat snakes, rats, and raccoons can climb into a roost and prey on the bats while they are roosting during the day. We install predator guards at the bases of roosts to help prevent access to the roost. So selection of an artificial roost has to take in predator access into the equation. That is why we don’t install bat houses on trees but prefer free-standing poles.“

Three weeks after the first box went up at Zoo Miami, bats had already moved in.

Watching Success Take Flight

Over time, the results surprised even the scientists.

Eight years after installation, ten custom bat boxes around Zoo Miami sheltered more than 100 Florida bonneted bats. That made it the largest known population in Miami-Dade County and the second largest in the entire range of the species.

Some boxes held as many as fifteen bats at once. The animals were not just using the boxes. They were thriving in them.

The success spread beyond the zoo. In 2025, more than one hundred bats were recorded using 24 additional boxes installed in other locations by the lab.

What started as an experiment became a model for saving a species.

Science Meets Community

The Miami Bat Lab does more than build shelters. It builds understanding.

Through a program called Bat Ambassadors, scientists and educators work with local communities. They teach people why bats matter, how to live alongside them, how to plant bat gardens that grow insects for the bats, and how residents can help protect this rare species.

Community members learn how to support bat-friendly spaces and even how to help monitor bat boxes. Conservation stops being something distant and becomes something personal.

When people understand a species, they are more likely to protect it.

Why This Work Matters

The Florida bonneted bat plays a quiet but important role in Florida’s ecosystems. It eats insects, helping control pests and support healthy landscapes. It has also been shown to target crop pests, helping suppress these species and likely offsetting pesticide use. But its story is about more than one species.

It shows what happens when science, creativity, and cooperation come together. It shows the Endangered Species Act recovery work in action. It proves that conservation is not just about saving what is wild, but about adapting how humans live with wildlife.

It reminds us that extinction is not inevitable when people choose action over indifference.

Somewhere tonight, a Florida bonneted bat will slip into a shelter designed just for it, safe from storms and heat and loss.

That shelter exists because scientists refused to accept disappearance as the ending.